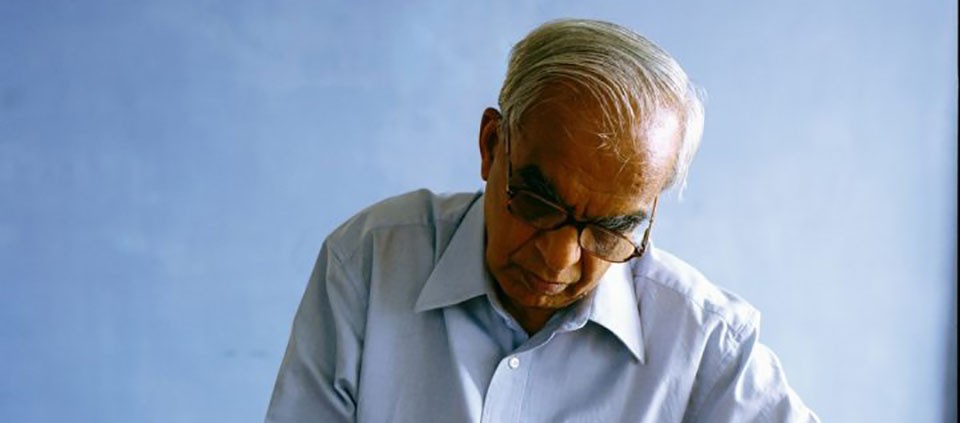

Remembering Sir

Growing up in a conservative Brahmin family, I had a deep desire in me to break out of conventions. My keen interest in philosophical inquiry attracted me to the idea of yoga, but I feared the orthodox teachers who were competent in yoga thought. Until I first met T. K. V. Desikachar.

I stood before a man who took me in with his eyes and spoke to me in a light vein. Gone was any trepidation I might have had or any suspicion that I was under scrutiny by a learned authority on a traditional subject. I could talk to him, eye to eye. And, of course, I felt comfortable about the fact that he was wearing trousers and a shirt, like me. Our first meeting went like this:

He: So, what have you come here for?

Me: I am seeking liberation.

He: Oh, we don’t sell that here.

Me: Oh, I don’t mean it like that, Sir. I wish to learn yoga and understand more about the idea of liberation.

He: Would be better, you get interested in a regular practice. Learn, practice regularly at home. Then let’s see what transpires.

I became a steady student of his and of yoga. After a couple of years, I asked him the same question once more. He began with a question.

He: What happens to you, when you practice?

Me: I become quiet and attentive. Actually, I also quite enjoy doing my practice.

He: Just stay at it! Something is bound to happen!

I had learned to trust him as a teacher and accepted his cryptic reply. In the course of time, something happened—something that I hadn’t expected at all to be the result of my quest. It was an understanding, which turned out to be a liberating experience for me: The goal isn’t there for us to reach it and claim that we have been successful. It is there to goad us on, to keep us on the path of continuous practice. Drawing on a Yoga Sutra from the fourth chapter, he told me that the fruit develops to its full taste when the time is ripe.

A Skillful Therapist

Of course, such understanding would never have dawned on me if I had not learned yoga from Sir, as all his students in India called him. His brilliant exposition and handling of the Yoga Sutra brought me close to the ideas which I had been seeking all along.

T. K. V. Desikachar had a convincing way of bringing out the inseparability of philosophy and practice. The way I had understood philosophy, it was knowledge-seeking, which relegated one to the armchair. For the first time in my life, I had a glimpse of a true philosophy of life, encompassing a beautiful knowledge that is not merely convincing but also holistic; not only grand for the mind, but also for all aspects of our being. Most certainly, Patanjali has given this knowledge many centuries ago and many a commentator has explained it many times over. But it was the exemplarily lucid manner in which Sir taught that really bound me to the subject and gave me the motivation to go deeper.

“The clarity of your perception is the only real proof that your mind is serene,” Sir used to say, interpreting the Yoga Sutra 1.4, as he goaded me on to seek this clarity and not be worried about the question of convention.

Being a sceptic by nature, I always associated his profound therapeutic skills to professional experience rather than any clairvoyant insight. One evening, at around 6:00 pm, Sir and I walked together into the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM), his nonprofit yoga center. In the early '80s at the KYM, around 10 people would have registered for a consultation each evening. Many people were on the porch, standing or seated in the wicker chairs, waiting. We walked past them into the building and entered his consultation room. I sat opposite him at his desk and, after a moment, he said,“Bring in the man with the severe stomach ailment.”

I went out to the secretary sitting at the entrance desk and asked him who this person might be. He fished out the consultation sheets, which had been filled out by the people waiting outside and showed me the person in question. After the first few sentences during the consultation, it became obvious to me: This man had never seen Sir, and Sir had never seen him before or heard anything about him. The mere glance while walking by a group of people in the dusk had been enough for him to spot the type of suffering that one of them was going through.

Over the years, there were many occasions when I was fortunate enough to glimpse Sir’s extraordinary ability to instantly understand what ails a person and what would be a good solution. In other words, I learned from a man who could, in a flash, get to the essence of an issue and envision the solution, too. For me, this was philosophy in action, knowledge with relevance to living.

An Intuitive Teacher

Knowledge is not merely a means to see clearly beyond the world, but first and foremost, to see the world before us clearly. Was this not what Sir was teaching us in the second chapter of the Yoga Sutra?

One day, Sir told me that I should teach yoga to children who were mentally handicapped. I found the idea abhorrent. I knew that I had neither the patience nor the concern for these children to enter into their world, much less reach out to them. I managed to put out a flat refusal without sounding offensive.

Fortunately, he did not take it for impudence on my part and seemed to accept my decision. However, he came back to his suggestion after a few days, to which I again refused politely. The third time he brought up the topic, there was an insistence and urgency in his voice and this time I complied, making sure he noticed that I was doing so against my wishes.

A year went by in which I spent two days of every week at Vijay Human Services, doing regular classes for the children, in groups as well as individually. I realized I was doing my work with great passion and enjoyment. After my second year of work with the children there, I realized something had happened to my approach towards knowledge. I had begun to grasp that knowledge has to be practical, it has to be applicable, it has to be shared, and it has to bring joy. Otherwise, it is a burden for the mind as well as the soul. In teaching the children, I was unburdening myself, becoming a lighter-hearted human being and learning to really look at the world. This experience shaped me and nourished me. And, of course, in retrospect, Sir’s insistence that I teach these children became clear proof of his insight. His insistence was a blessing in disguise for me.

A Friend in Need

Today in the West, yoga is a household word and many people think it is something that was discovered in the United States, based on some ancient ideas from India. However, in the late 1980s when I moved to Germany, the home of my wife, yoga was seen differently. Getting to teach yoga was not easy and I had a very difficult start. Eventually, I found an institution that hired me to teach on a regular basis.

A day before my lessons were scheduled to start, some people attached to the institution protested, alleging that yoga was an occult practice based on Hinduism, which could lead people away from their Christian values and into sorcery. I was feeling dampened and isolated with my yoga skills when, one day, to my utter surprise, I received a long letter from Sir with loving words of comfort and encouragement. During his next visit to Europe, he made a point of visiting me.

A new level of exchange between us began. He was not merely a teacher now, but someone who understood me and my life as an Indian living in a foreign country. Despite this, he showed great understanding towards my son growing up in a motley of cultures, and my wife, doing an Indian dance art in a foreign culture—drawing on his links and engagements with the West through yoga, his students, through J. Krishnamurti, and through his brother living in France. In my initial years of struggle in the West, his emotional support greatly helped me to come to terms with the European ground beneath my feet. Getting this level of personal attention from him was of very great value to me.

A Free Man

Over the years, I organized many teaching sessions for Sir in Germany. He would stay in a hotel in my vicinity and teach in a hall I had rented. He travelled with a small and simple piece of hand luggage, never more, even if he was on a one-month trip to different countries. He would always walk out through the customs gate at the airport as though he was merely stepping out of a building in Chennai—simple, relaxed. There would be no trace of any of the usual tension of a person crossing borders and customs. I have never once seen him buy anything for himself on any of these trips, apart from a razor, a piece of soap, or something similar. The fancy consumer goods of the West made no impression on him. But whenever we went to meet someone, even if it was someone he did not know, he would make sure that on the way, we would buy a nice gift for them.

At the end of the stay, he would opt to have his honorarium, after deducting all these expenses, transferred to his bank account. He declined to deal with European cash and kept himself free of the issue of money. I found this attitude most impressive. The simplicity that he exuded is almost a synonym for freedom. In this way, he has given me and many other people a taste of what it is to be light and free.

I met Sir when he was 49 years old. Over the years, his gift to me was immeasurable. All my knowledge of yoga is derived from him. He opened up to me when I came to him as a distraught engineering student with no conviction in what I was doing. He helped me succeed in my profession by contributing to my reputation in Europe. He supported me emotionally as a private person, showed deep interest in my private welfare, and understood me and my life as only a friend can. It’s a major loss that he is no more. It’s a major gain that there are so many individuals across India, as well as the world, who have had a personal and deep learning connection with him.

R. Sriram began to teach yoga systematically in 1977 in Chennai, his hometown, with T.K.V. Desikachar.

Full Bio and Programs